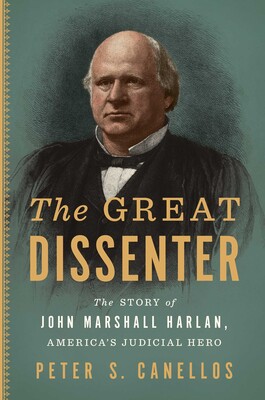

The Great Dissenter: The Story of John Marshall Harlan, America’s Judicial Hero

- By Peter S. Canellos

- Simon & Schuster

- 624 pp.

- Reviewed by Mark Gamin

- July 29, 2021

A compelling look at an unusual — and unlikely — civil rights champion.

As are we all, John Marshall Harlan was a product of his time and place, the latter being, in his case, Boyle County, smack dab in the middle of Kentucky, where he was born, and where he later graduated from Danville’s Centre College. Harlan’s time began in antebellum America, when slavery was a fact of life. His family owned slaves and, as an adult, he did, too. He was also anti-abolition (preferring gradual emancipation) and opposed the slavery-ending Thirteenth Amendment.

So, his later reincarnation of sorts as a hero of the civil rights movement, as well as his present-day recognition as a seer of the law — one who was in the minority on multiple issues but whose judgment was later proven prescient — is a remarkable part of American legal history. His tale gets a sensitive and balanced telling in Peter S. Canellos’ The Great Dissenter: The Story of John Marshall Harlan, America’s Judicial Hero.

Before the Civil War, Kentucky was bitterly and evenly divided on the matter of secession. Yet despite being a slaveowner, Harlan was also an ardent constitutionalist who could not abide the thought of disunion and who served for a time as a lieutenant colonel in the Union Army.

After the war, he became Kentucky’s attorney general and twice ran, unsuccessfully, for governor. He had no political home of consequence (before the war, he had belonged to the Know-Nothings; after, to the Conservative Unionists) until he joined up with the Republicans, renouncing many of his previous positions on race, slavery, and states’ rights in order to do so. In 1877, he was nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court by Rutherford B. Hayes and (not without opposition) was confirmed.

The subject of Canellos’ book isn’t just one man, but also the incredibly strange, heartbreaking complexity of race relations in America during that man’s lifetime. In order to demonstrate that complexity, Canellos has at hand another character, the ideal foil for his protagonist — John’s half-brother Robert Harlan.

They had the same white father, James Harlan, but Robert’s mother was an enslaved person, and Robert, too, held that status in the Harlan household. The light-skinned Robert was educated by the other Harlan brothers and eventually allowed to buy his freedom. In what Canellos calls “the odd etiquette that surrounded the slave culture,” Robert’s parentage was assumed but never discussed:

“It was a form of ritual denial, the product of an institution that defied moral boundaries and expectations.”

Robert turned out to be a kind of genius as a horse breeder, businessman, and political fixer. He traveled west and made a fortune in the California Gold Rush. At one point, he was “vastly more successful than any of his white brothers.” Robert and John were close (Robert’s letters to John survive, but not John’s to Robert), and Robert eventually made it a personal priority to help his brother get onto the Supreme Court.

Once there, John Marshall Harlan was not always right and not always consistent. But he was able, for the most part, to escape what Canellos calls the “willful obtuseness” of his fellow justices (including that sainted popinjay, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.) not just in civil rights cases, but in other cases arising on the cusp of the modern legal era — including those involving matters of antitrust, income tax, and the incipient American empire.

Plessy v. Ferguson was the 1896 case that upheld the constitutionality of “separate but equal” public facilities for whites and Blacks. As Canellos writes of the doctrine: “In equal parts ridiculous and ingenious, it was designed to provide a legal fig leaf for segregation.”

“Our Constitution,” Harlan wrote in his fierce dissent of Plessy, “is color blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among its citizens.” It still makes for stirring reading today; no wonder Thurgood Marshall, the first Black Supreme Court justice, called Harlan’s dissent his “Bible.”

Just down the road from Harlan’s alma mater is another illustrious Kentucky institution of higher learning, Berea College, which became the subject of Harlan’s last statement on a civil rights case. Berea, a private school, taught Black and white students side by side, but in 1904, the Kentucky legislature outlawed such “comingling.” In Berea College v. Kentucky, the high court, using, as Canellos says, “legal somersaults to accommodate racial prejudice,” found the state law constitutional. The upstanding Justice Holmes concurred.

But Harlan again dissented. It took 50 more years, but his views were finally adopted by a unanimous Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, which repudiated the notion of “separate but equal.” That, Canellos writes, is Harlan’s great legacy:

“The fact that one white man, rather than none, believed that the national charter could support a diverse nation built on equality under the law — in fact, demanded it — sustained the faith of Black people for generations.”

Late in the book, Canellos pulls the rug out from under the reader: Maybe Robert Harlan wasn’t the son of James Harlan after all. But who cares? Robert was an extraordinary character in his own right and probably deserves his own book.

On second thought, maybe this engrossing work, with its wealth of information about Robert’s life, is his book, as well as John’s.

Mark Gamin is a lawyer, writer, and editor. He is currently writing a book set in the middle of Idaho, the working title of which is The Middle of Idaho. Physically resident in Cleveland, in his mind, Mark is often at his small farm in Appalachian Ohio, on the very edge of civilization.

_80_122.png)