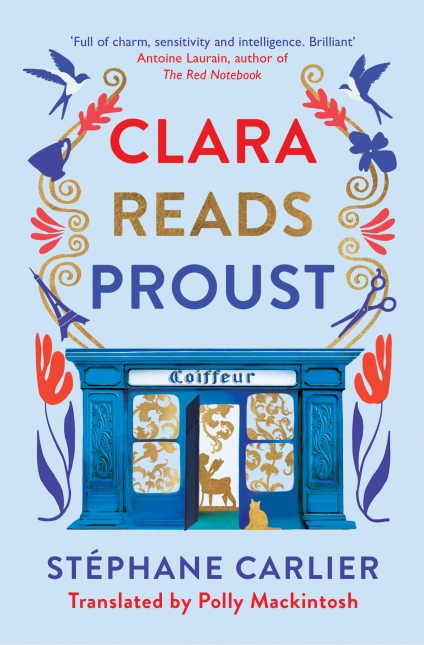

Clara Reads Proust

- By Stéphane Carlier; translated by Polly Mackintosh

- Gallic Books

- 192 pp.

- Reviewed by Anne Eliot Feldman

- May 29, 2024

A left-behind novel ignites the life of a young hairdresser.

Stéphane Carlier’s Clara Reads Proust is a one-of-a-kind novel about the power of literature to spark transformation in a reader’s life. Tinged with humor and peppered with quotes lifted straight from Marcel’s own writings, this engaging story set in the charming French village of Chalon-sur-Saône provokes thought as it inspires.

Protagonist Clara has a handsome firefighter boyfriend, loving parents, and a steady job in France’s gentle Loire Valley, but nothing assuages her self-doubt. Her doting beau is a man she no longer desires, and her job as a hairdresser — at a third-rate salon “whose entire length can be viewed from the till” — makes her life feel like “a flat succession of days.”

Writing in a third-person point-of-view that shifts easily between omniscient and close, Carlier paints Clara’s fellow employees with their own colorful struggles. Obsessively romantic boss Madame Habib drenches herself in so much Shalimar perfume that it “permeates the whole room and has become as much a part of the brand as the white marble-effect tiles and the two chiming notes of the doorbell.” For hapless Nolwenn, hairdressing doesn’t come naturally: Her DIY perm-cut-into-a-bob experiment looks more like a Halloween costume. And Patrick, the place’s sole male stylist, is often tardy and has anger-management issues but, as Madame Habib concedes, “is responsible for whatever little reputation her salon has.”

In short, Cindy Coiffure has seen better days. Hence, it’s no wonder that when the hot repairman finally shows up after a 10-week wait, the staff is riveted:

“He is magnificent, a kind of perfection…It makes you wonder what he’s doing repairing display cabinets in Saône-et-Loire instead of walking the catwalk in Paris or Milan. The scene at Cindy Coiffure right before lunch is a sight to behold, the five women in the salon practically rooted to the spot as they watch him crouch, kneel and then lie down on the tiles, contorting his body to get his hand underneath the cabinet, which he repaired far too quickly.”

The irony of her own lack of contentment isn’t lost on Clara as she fluctuates between knowing she should be happy and wanting more. “On the horizon the clearing skies are drenching the Saône-et-Loire countryside in gold. At the root of her distress are several questions,” writes Carlier. “Is this as good as it gets? Are we as happy as we’ll ever be?”

When a client accidentally leaves behind his copy of Proust’s 1922 In Search of Lost Time, Clara puts the book in a drawer, where it stays “for precisely five months, twenty-nine days, two hours and forty-seven minutes.” But then, in a low moment, she picks it up. It’s not an easy read. Her initial impression is mostly curiosity for “a book that was written over a hundred years ago by a man who never left his bed, a book with interminable sentences and which she feels, for a reason she still cannot understand, will make her stronger…But still. He could start a new paragraph a little more often.”

As Clara methodically peruses the seven volumes of Proust’s 4,000-page masterpiece — officially the world’s longest novel — it dawns on her how unlikely it is to have connected with the book.

“Proust. Until now that mythical name had meant as much to her as one of those cities — Capri, Saint Petersburg — in which she knew she would never set foot.” But when things get even worse, Proust becomes the life raft that will save her, as he prompts her to realize “it is possible to live differently; there are other options: you don’t have to go out every day, and cut, curl and perm the hair of women you wouldn’t otherwise meet in a million years.”

Considered among the greatest novels of the 20th century, In Search of Lost Time broke with the plot-driven conventions of its era to focus on the nuances of one man’s story from boyhood to maturity to his embrace of the right vocation. Carlier knows Proust is not for everyone — “People aren’t used to feeling things in such a way in day-to-day life. And adapting to that level of subtlety is what requires effort on the part of the reader” — but he works for Clara because this is her journey, too, and nothing matters more. As Proust wrote:

“Our wisdom is the point of view from which we come at last to regard the world.”

While this is Carlier’s eighth novel, it is his first to be translated into English (by Polly Mackintosh). Clara Reads Proust offers an edifying homage to one of France’s most respected writers and a real-life ending that makes us think. We finish the book with the sense that pushing beyond what we know can elevate our perspective, give us joy, and awaken innate talents that might otherwise have lain dormant forever.

Formerly employed by the Library of Congress and the defense industry, Anne Eliot Feldman is currently at work on a writing project of her own.