Concerning the Future of Souls: 99 Stories of Azrael

- By Joy Williams

- Tin House Books

- 176 pp.

- Reviewed by Samantha Neugebauer

- July 17, 2024

An insightful, sometimes inscrutable collection of tales.

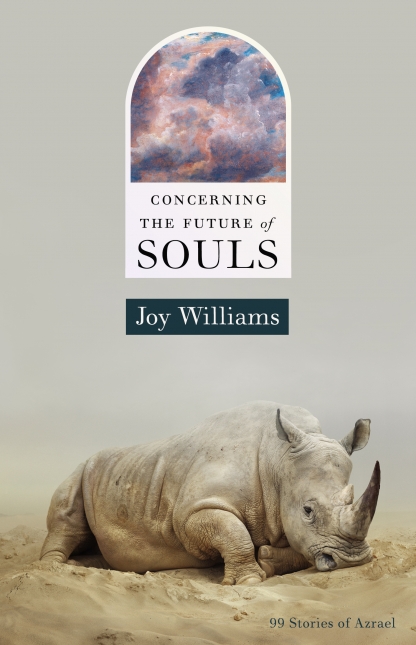

The cover of Joy Williams’ latest work shows a rhinoceros wallowing in the driest sand imaginable. A murky blue-grey fills the background. It’s a strikingly singular and bleak cover for a strikingly singular and bleak book. Told in a loose collection of 99 vignettes, Concerning the Future of Souls is a follow-up to 2013’s Ninety-Nine Stories of God. Like its predecessor, this slender new volume is at times sublime, elegiac, and baffling. It features extremely short tales of everyday existence for ordinary folks, non-human animals, and well-known figures, including Jung, Nietzsche, Pythagoras, and Bach, alongside comic and melancholy exchanges between Azrael (the Angel of Death) and the Devil.

In Williams’ cosmic vision, Azrael faces many quandaries. “Could it be that souls are leaving a person before the body dies?” he asks the Devil, who assures him that it’s possible since “the soul wants out [because it’s] not being fed what’s necessary.” Azrael becomes more anguished. He knows “indwelling anywhere” is “impossible,” with “the mountains [having] been stripped of their holiness” and “the oceans of their mysteries.”

While other writers might’ve made this conversation a jumping-off point for the narrative, Williams chooses to position it near the end. In the opening vignettes, she instead weaves through various times, places, and planes, collecting evidence for the Devil’s eventual admission, as if we need further proof of the collapse of our physical and spiritual realms.

But all is not dreary and didactic. Being a fly on the wall during Azrael and the Devil’s chats is quite fun. Satan, though wise, often acts like a cantankerous grandpa with too much time on his hands. “Everything he stood for was running along on its own, requiring very little involvement on his part,” writes Williams, and “now he was a sop, a concession, an afterthought.” Yet, it’s also possible that his latter lament is simply “the inner voice talking, the still small voice, that little piece of God caught inside him like a fish bone, trying to make him feel bad.” Regardless, he and Azrael are at their best when they’re gossiping about Death or God.

For the uninitiated, it might not be obvious how to tell the Devil, Death, and Azrael apart. In short, Azrael works for Death, while the Devil and Death have a more complicated, uneasy relationship. At one junction, either out of cruelty or boredom, the Devil tells Azrael that there’s only “a difference without distinction” between Azrael and Death, which is perhaps an attempt to nudge the reader to consider our complicity in the life and death of others.

We also learn that Azrael “travels in different circles” than Jesus, which is funny since Azrael isn’t exactly a familiar name in Christianity. He is, however, one of the four main archangels in Islam (although there’s some argument about whether Death and Azrael exist in that faith). For her part, Williams has always dipped into the Abrahamic religions — and Buddhism — indiscriminately, plucking what she needs from each. Her characters are similar. In 1982’s “Taking Care,” one of her most beloved stories, Jones, a Christian preacher, recounts the tale of Buraq, Muhammad’s horse, “who could stride out of the sight of mankind with a single step,” as a bedtime story for his baby granddaughter.

Williams is the author of 13 books. She’s received a Guggenheim Fellowship and Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction and has been a Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award finalist. Still, more often than not, she is considered a writer’s writer, with most non-writers encountering her voice through her 2003 guide to the Florida Keys, which included an unusual (for guidebooks) lament against tourism and the ensuing degradation of the area.

All this is to say that her most scathing commentary is typically found in her nonfiction, such as in both the aforementioned guidebook and in her essay collection Ill Nature. Her fiction explores many of her same preoccupations (the afterlife, the loss of the natural world, etc.), albeit with more restraint and tautness. Within Williams’ oeuvre, Concerning the Future of Souls appears to occupy a middle ground, blending imagination with indictment as if the author cannot help but let her disappointment in her fellow humans spill over a bit.

Samantha Neugebauer is a lecturer at NYU in DC and a senior editor for Painted Bride Quarterly.