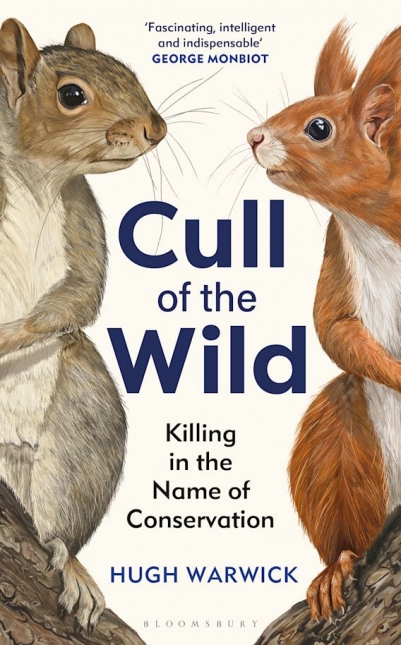

Cull of the Wild: Killing in the Name of Conservation

- By Hugh Warwick

- Bloomsbury Wildlife

- 304 pp.

- Reviewed by Christopher Lancette

- June 26, 2024

Is there a better way for us animals to coexist?

You know the author of a new book about the ethics of killing animals is onto something monumental when he makes you ponder whether even the parasitic avian vampire fly deserves to live. The insect lays eggs in the nests of Darwin’s finches that turn into maggot meat for the unsuspecting birds.

“Death to the vampires!” most readers — and this reviewer — may be quick to shout.

But not so fast, Hugh Warwick implores in Cull of the Wild: Killing in the Name of Conservation. “I do think it is important that we recognize that killing for conservation is not an absolute right or wrong,” he writes.

Warwick’s response comes with a request: “We have to admit to a degree of straightforward species preference.”

In other words: Let’s be honest enough to say that we like finches more than flies — and that we use our own values and biases to make choices about who gets to live and who deserves to die.

Warwick isn’t immune from such prejudice. The ecologist and writer is also the official spokesperson for the British Hedgehog Preservation Society. He recognizes his own bias, though, and wrote Cull of the Wild because he believes “we deserve to have an honest conversation about conservation.”

Such a chat starts with the principle that “human animals” should look at “non-human animals” (we’re all animals) in a more conscious way, even in the words we use. Wildlife managers, for instance, use the term “culling” to refer to removing a particular species from an area.

The more accurate word is “killing.”

If we can get the language right, we may actually have a chance to successfully confront the myriad conservation conflicts Warwick lays out in his book. The common denominator here is the question of what role humans should play in determining the fate of everything from penguins to deer to dormice. Do we play God, Warwick asks, and, if so, how? Or do we sit back and let nature run its course?

And what do we do when one species is wiping out another? Like when the British go gaga for red squirrels but choose to terminate their nemesis, grey squirrels.

Warwick understands the answers aren’t clear-cut and that suggesting otherwise is disingenuous. Try any number of the mind-jarring thought experiments he unleashes. Would we kill one fat man to save the lives of multiple people tied to a subway rail? Go laissez-faire at the Louvre and let it burn because more art will be made in the future? How would we react if government officials told us they needed to kill our dogs to save 40 others?

Humans began altering the landscape — and all the non-human animals in it — from the moment we appeared, causing one species after another to suffer and go extinct. Warwick yearns to provide a definitive answer — a manifesto — about how to clean up our mess. While he perhaps too harshly berates himself for falling short on the effort, his search for ethically consistent conservation lays trail markers that can help us find our way.

Warwick dissects Ignoring Nature No More: The Case for Compassionate Conservation by Marc Bekoff, an acclaimed American ecologist and ethologist. He lauds the book’s four tenets — starting with “Do no harm” — as principles full of philosophical potential. They can, however, fail in the real world, where the act of not killing can sometimes lead to more death. (Think of large numbers of deer minding their own business but destroying a woodland that provides food and shelter to countless more lives.)

Developing compassion is a good start, but Warwick points to another set of guidelines that may be even more useful in resolving conflicts between non-human animals and us. The University of British Columbia and the B.C. Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals hosted 20 experts and established principles that start by looking through the proper end of the telescope:

“Begin wherever possible by altering human practices that cause human-wildlife conflict and by developing a culture of coexistence.”

One example? Don’t point fingers at wolves for wandering outside protected park boundaries and occasionally dining on a rancher’s sheep when we’re the ones who obliterated their natural habitat, thereby forcing them to look elsewhere for food. (Ecologists often opine that wildlife management is really about people management.)

The British Columbia consortium calls on humans to consider six more notions, including an emphasis on doing everything possible to mitigate pain and suffering when the lesser of two evils is culling/killing.

“A frustration I have,” the group’s peer-reviewed publication’s author, Sara Dubois, tells Warwick, “is the lack of reverence to individual life.”

Maybe if we could just start there — recognizing that non-human animals inherently deserve their own place on our planet — we wouldn’t need to do so much killing in the name of conservation.

Christopher Lancette is a Silver Spring, Maryland, freelance writer focusing on nature and the environment. Read more of his work and find his social-media links here.

_1_80_120.png)