Never Say You’ve Had a Lucky Life: Especially If You’ve Had a Lucky Life

- By Joseph Epstein

- Free Press

- 304 pp.

- Reviewed by Patricia Schultheis

- May 16, 2024

A noted scribe recalls his charmed existence with candor and gratitude.

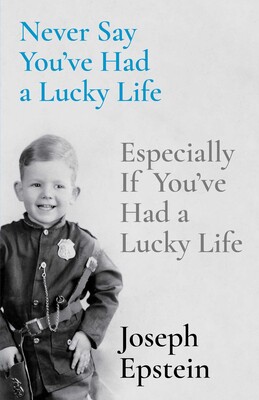

The truth of the old adage “A picture’s worth a thousand words” needs no greater proof than the cover photo of Never Say You’ve Had a Lucky Life, an autobiography by Joseph Epstein, one of the nation’s most prolific and honored writers. The image is of Epstein looking mighty pleased with himself, as any 4-year-old lad in a snazzy Royal Canadian Mounted Police uniform replete with badge, Sam Browne belt, and cap pistol would be. The optimism evinced in young Epstein’s happy grin courses throughout his life’s story.

“In this book,” he tells readers, “I more often recount my own extraordinary good luck in the time in which I was born, in the parents to whom I was born, in my education, and much more.”

Epstein is a lifelong Chicagoan; aside from seven years in Arkansas and New York, the windy city has been his home, and its hurly-burly variousness nourished his childhood curiosity, fostered his intellectual growth, and, through friendships with such outstanding scholars and writers as Edward Shils and Saul Bellow, supported his professional development. One of the unique insights that Never Say You’ve Had a Lucky Life gives readers is on the nature and necessity of male friendships.

Maybe because his unabashedly practical parents didn’t waste energy on anything they could do nothing about, or perhaps because he grew up before therapy-driven inwardness became commonplace, the focus of Epstein’s autobiography is principally on his career rather than his personal life. Or maybe he simply took his father’s advice to heart:

“Your responsibilities to your sons include feeding them and seeing they have a decent place to live and helping them get the best schooling they’re capable of and teaching them right from wrong and making it clear they can come to you if they’re in trouble and setting them an example of how a man should live. That’s how I looked upon my responsibility to you and your brother. But for a man, work comes first.”

And work Epstein did; he had no other choice. By the time he was 23, he was in the Army, married, and the father of two stepsons. Shortly thereafter, he was back in Chicago, working for Kiwanis Magazine, and the father of a newborn. And shortly after that, Epstein was in New York, writing for the New Leader, a publication with a socialist slant, and again a father.

By 26, he had four sons, was living in Flushing, Queens, worked full time, and began attempting to do his own writing. This was followed by a stint in Little Rock working in urban-renewal and anti-poverty programs, jobs that ultimately set him on a path as a writer and editor. “Such advances as I have known in my life have come about owing to my writing,” he reflects.

When Harper’s published an article of his on urban renewal, Epstein was catapulted into the national spotlight and eventually into a position at Encyclopedia Britannica. By this point, the family was back in Chicago, where Epstein and his wife divorced. He suddenly found himself the single father of four boys aged 14, 12, 8, and 6. “Asked what phrase my children might have heard most frequently from me when they were growing up,” he writes, “my guess is that it might be ‘I’ll be there as soon as I finish this paragraph.’”

Given that Epstein’s situation was unique — it was unusual in the 1960s and 70s for a man to parent solo — it would’ve been nice to hear more about how he managed. Surely, a pipe must’ve occasionally burst, the car’s ignition failed to turn over, or the math teacher requested a meeting. How did he cope? Perhaps including such reflections would’ve demanded a different sort of book altogether, one inconsistent with Epstein’s characteristic detachment.

Still, his natural wit permeates the work, as when he observes of a fraternity brother, “Short, pudgy, already nearly bald in his last year at college, as if the fates, in endowing Sammy so much financially, had exacted his youth in exchange.” Elsewhere, Epstein’s deceptively simple language becomes almost elegiac:

“I remember in late autumn returning home from football practice at Chippewa Park, in my shoulder pads and orange-and-black team jersey, and in the darkening evening sighting several fires of burning leaves along the curbside gutter of Campbell Avenue and thinking how beautiful it, and the world I knew with it, all was.”

Now 87, Epstein remains enthralled by “life’s variety, its richness, its surprises and astonishments” and is somewhat dismayed to realize that “the minutes, hours, days, months, years pass at roughly the same speed, and it is only the decades seem to fly by.” Departed those decades may be, but they return in lovely recollection in these pages.

Patricia Schultheis is the author of 40 published short stories, including the award-winning collection St. Bart’s Way. She is also the author of Baltimore’s Lexington Market, published in 2007, and A Balanced Life, published in 2018. She is the recipient of numerous awards and honors and is a member of the National Book Critics Circle. She lives in Baltimore.