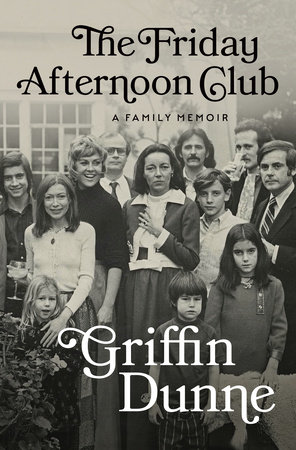

The Friday Afternoon Club: A Family Memoir

- By Griffin Dunne

- Penguin Press

- 400 pp.

- Reviewed by Diane Kiesel

- July 1, 2024

An affecting, poignant recollection of life among the Hollywood literati.

As was fitting for a man who made a living as a broadcast executive in the early days of television, Dominick Dunne created a midcentury family straight out of “The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet” or “Leave It to Beaver.” There was the beautiful, wealthy wife; three picture-perfect children; a five-bedroom home in Beverly Hills with an inground pool; a Mercedes-Benz; and parties populated by Sean Connery, Natalie Wood, John Huston, Truman Capote, Billy Wilder, and a young Dennis Hopper.

But as eldest son Griffin recalls in his touching, bittersweet memoir, The Friday Afternoon Club, the family was as fake as the Nelsons and the Cleavers. Dominick Dunne was a deeply closeted, name-dropping drunk who worshipped at the altar of overpriced restaurants. His world revolved around Hollywood’s A-list to the point where he would host lavish parties on school nights and send his kids packing to a hotel with their nanny to get them out of the hair of his famous guests.

Meanwhile, Griffin, who never made it past 10th grade, struggles with dyslexia — barely understood then — and is shipped off to an East Coast boarding school at age 11, where he becomes an expert cheat and liar, gets flogged for minor infractions, and endures a sexual come-on from a teacher. Younger brother Alex suffers from mental illness so severe he thinks he sees Christ and contemplates suicide. Griffin’s mother, Ellen (known as “Lenny”), slowly fades into oblivion, a victim of relentlessly degenerative multiple sclerosis.

Dominick and Lenny divorce, and Dominick’s alcoholism costs him his job and his coveted Tinseltown status. With nothing left to lose, he heads to the Pacific Northwest to dry out and remakes himself as a novelist. Back in sunny California, Dominick’s brother John Gregory Dunne and John’s wife, Joan Didion, write break-out books and supplant Dominick and Lenny as the new Golden Couple in the world of boldfaced names.

As the 1970s fade into the 80s, Griffin and his baby sister, Dominique, launch their own acting careers and love to party. Each Friday, Dominique’s acting class — including then-fledgling actors George Clooney and Timothy Hutton — gathers until the wee hours in the Dunne back yard as part of the “Friday Afternoon Club.” Then, in what hits the family like an atomic blast, Dominique — only 22 and on the cusp of true stardom — is strangled to the point of brain death by a boyfriend she’d tried to dump. The family is forced to pull the plug. When her killer, John Sweeney, a sous chef at Ma Maison, walks away from the crime with a slap on the wrist, it becomes the signature event that divides the book into a stark Before and After.

Given the patina of Hollywood make-believe that hangs over this memoir, it’s fitting to recall a line spoken by Glenn Close’s character, Iris, in the 1984 movie “The Natural.” She tells Robert Redford, who stars as deeply flawed baseball player Roy Hobbs, “I believe we have two lives…The life we learn with and the life we live with after that.” The second half of The Friday Afternoon Club describes the horror of Dominique’s death and how the Dunnes chose to live with it.

The 1983 trial is still revolting more than 40 years later. The justice system failed to understand the dynamics of domestic violence. A woman is in grave danger when she leaves an abusive relationship because the batterer realizes he’s losing control over her. Yet at trial, it was Dominique who was painted as the abusive partner. The defense attorney depicted her as a drug-abuser who hurt sensitive Sweeney by rejecting his love; his crime was one of passion.

The court made evidentiary rulings favoring the defense, including preventing the jury from hearing from a former Sweeney girlfriend whom he beat so badly, she landed in the hospital. The judge barred testimony from Lenny about witnessing Sweeney’s abuse of Dominique yet allowed him to testify while holding a Bible. Not surprisingly, without a full picture of Sweeney’s character, and in light of the “blame the victim” defense, the jury returned a verdict of voluntary manslaughter. The killer was out of prison in three years.

In the aftermath, Dominick became a prominent voice for victims — particularly women — through his reporting about crime in Vanity Fair, which published his account of his daughter’s trial and, later, his pieces on the O.J. Simpson trial. “At great cost,” Griffin writes, “my father found his voice as a writer.” Lenny found purpose as a victims-rights activist. Once Sweeney emerged from prison, the Dunne family kept close tabs on his new girlfriends and jobs, but eventually Griffin stopped and focused instead on his sister’s memory. “I can let go of the hate, but will never let go of missing her,” he writes. “That is my choice.”

It has been a long and winding road to adulthood for Griffin, who inherited the family genes for turning a phrase. In a hilarious vignette, he recalls a father-son baseball game in grade school where he was humiliated in front of his best friend, Cody, son of Jack Palance, the celluloid gunslinger. Dominick’s awkwardness meant he was the last dad chosen for the team and was stuck in the Siberia of far-right field, where he kibbitzed with Natalie Wood while munching a hotdog. Palance stepped up to the plate and rocketed a hit straight toward Dominick, who tossed the wiener, bent down to pick up the ball he’d missed, and then inexplicably threw it at Wood.

The fans were doubled over with laughter, but not Griffin, who suffered as his friends imitated his inept father fumbling in the grass. Cut to years later, when Dominick and Griffin, now an adult with an acting and producing career of his own, are having lunch, and Dominick reveals that he’d been awarded the Bronze Star for valor during World War II. It seems that he and a fellow infantryman had entered the line of fire to rescue and then carry two injured comrades for miles through the dark Ardennes Forest.

“My fragile identity…[had been] tied to a father who couldn’t throw to third and gave me two French poodles named after famous homosexuals,” Griffin writes. “It took me many years to understand what it meant to be a man, and by then I realized I’d been raised by one all along.”

Diane Kiesel is a former judge of the Supreme Court of New York. She is the author of Domestic Violence: Law, Policy, and Practice, published in 2017 by Carolina Academic Press. Her next book, When Charlie Met Joan: The Tragedy of the Chaplin Trials and the Failings of American Law, will be published in February 2025 by the University of Michigan Press.