The physician seeks to paint a more nuanced picture of Charles Lindbergh.

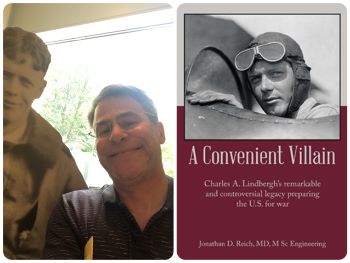

As a cardiologist on faculty at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Jonathan D. Reich is no stranger to research. The author of multiple articles for medical journals, he shifted his focus to historical research during the pandemic. After reading A. Scott Berg’s Lindbergh, Reich dove into studying the groundbreaking aviator and onetime presidential candidate. The result is his first book, A Convenient Villain: Charles A. Lindbergh’s Remarkable and Controversial Legacy Preparing the U.S. for War.

As a physician by training, how did you make the jump to writing a book?

Before I went to medical school, I was an aerospace engineer. I worked for the Navy designing airplanes and got a master’s degree. Part of my coursework was done in Israel. I had always known that Lindbergh had a legacy as an antisemite. So, during the pandemic, I read the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography Lindbergh. I expected to conclude this was his legacy. While reading the book, I had two realizations. First, although the author, A. Scott Berg, wrote an outstanding encyclopedic book, he had no appreciation for the aerospace contributions of Lindbergh’s life. I read a few other books about Lindbergh, especially about the period of his life when he lived in Europe and visited German air force facilities. I concluded that much of Lindbergh’s legacy was misrepresented. Second, Lindbergh’s legacy was too facile. He was a complicated man with a complicated, nuanced legacy. I decided that no one else would ever try to establish an accurate legacy of Lindbergh because it was unlikely there was another Jewish aerospace engineer who would want to spend years researching his life. I tried writing a magazine article but found it was impossible to condense the misrepresentations of Lindbergh’s legacy into 1,500 words. So, three years later, here it is: a biography of Charles Lindbergh’s life. I believe this is the first biography written by someone who is qualified to define his legacy.

What was your research process like?

During the pandemic, I had time to read nearly every biography I could find about Lindbergh and research references to see if statements had a valid basis. I also read dozens of other books about Europe in the 1930s, President Roosevelt, the 1940 presidential election, the Depression, and isolationism. I read [Lindbergh’s] journal and his wife’s journal. I read every New York Times article that mentioned Lindbergh and a host of other articles both critical and supportive of his legacy. As a physician, I concentrated on the two major medical advances that Lindbergh made: the first cardiac perfusion pump and his improvements in high-altitude aviation. I read about the different definitions of terms like “antisemite” and “Nazi sympathizer” and how they are applied to people from different eras. These figures existed and were sometimes dangerous, but using the definitions inaccurately hurts your credibility. Having a wife who is the daughter of a Holocaust survivor helped with perspective. Once the pandemic subsided, I made a trip to Yale University to go through Lindbergh’s papers. That was a fascinating experience; it felt almost as if I got to meet him.

What was the most interesting document you came across in your research?

The most interesting were the drafts of his speeches. Between September 1939 and December 1941, Charles Lindbergh gave five national radio addresses and 20 national speeches in opposition to the U.S.’ creeping involvement in World War II. The Yale archives contain not only the texts from which he read the speeches, some of which have handwritten edits, but the drafts of the speeches from his original handwritten notes (with his wife’s edits) to the final version of the speeches. But the most important document I came across was the letter from the U.S. embassy in Berlin on U.S. embassy letterhead in May 1936, asking Lindbergh to go to Germany to obtain information on Germany’s air force. Prominent historians have written that Lindbergh visited Germany because he admired the Nazis, and his intelligence work was “invented” later by his supporters. Finding this letter proved that no one “invented” Lindbergh’s intelligence work. It was the reason he visited Germany in the first place.

What made you want to take a closer look at Lindbergh’s life and politics?

I am continuously stunned by the poor academic scholarship and abject sloppiness that historians have engaged in when discussing this man. The more I write and the more feedback I get, the more examples I find. I not only find more misquotations and unsupported allegations, but I have found attempts at suppressing others’ opinions of him. We (defined as everyone, historians and non-historians, Jews and non-Jews) must be committed to the truth. He was a complicated, flawed man. I suspect we all are. Yet, his contributions to American security and medicine are remarkable and, in some respects, unparalleled. His flaws are discussed. But if we allow his flaws to supersede an honest discussion of his life, then we are truly doing a disservice to understanding the history of this country.

Did you uncover anything in particular that changed — or at least called into question — your previous understanding of him?

Reading his and his wife’s journals led me to an understanding of the times he lived in and the decisions he made. I tried strenuously to adopt a position of not judging people based on the ethics of our time. I spent a significant amount of time speaking to people who lived through the 1930s and 1940s to try and understand what it was like to be Jewish then.

Was Lindbergh a great man who had some flaws or a flawed man who did some great things? Does the distinction matter?

Fascinating question. Lindbergh was human. In his lifetime, his accomplishments are truly mind-boggling. However, he had major flaws — not just his legacy as an antisemite but in his personal relationships. He was not evil. He did not kill his son and he was not a Nazi. He was investigated by the FBI and exonerated. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover respected no restrictions on his investigative power and destroyed people when he had the chance. If he had found any evidence Lindbergh had any connection with any fascist power or organization, foreign or domestic, he would have produced it. He found nothing. I don’t think the distinction matters. We are all flawed. Few of us are great. Lindbergh’s contributions to the Allied effort to defeat both the Germans and the Japanese far outweigh his blemishes.

[Editor’s note: This article was written with support from the DC Arts Writing Fellowship, a project of the nonprofit Day Eight.]

Leah Cohen is a rising senior at Georgetown University, where she is majoring in English and minoring in journalism, and a journalism fellow at the Independent. Passionate about storytelling, Leah thrives on engaging with individuals and bringing their unique experiences to light through journalism. Outside the classroom and newsroom, she enjoys staying active through exercise and exploring her culinary interests in the kitchen.