The memoirist talks narrative tension, writing about real people, and the clarity of our younger selves.

In her exquisite new memoir, Loose of Earth, Kathleen Dorothy Blackburn, the eldest of five children, tells the story of her evangelical upbringing in Lubbock, Texas. To say it was unconventional is an understatement. Under the rule of a brilliant mother, the siblings are homeschooled with the Bible as their textbook, rejecting science for the teachings of the Lord. When Blackburn’s father is diagnosed with cancer at 38, her family turns to extremes — from diet to prayer to the seeking out, among other things, of a traveling preacher and a Malaysian holy man — instead of to medicine to save him.

What the family doesn’t know at the time is that no matter how many candles they light, God holds no power over the carcinogenic compounds — left by fire-fighting foams — that have contaminated the drinking water at the military site where her father had worked. Through the eyes of both the child she was and the adult she is, Blackburn unravels and retells the story of her father’s impending death, the willful and complex mother who desperately tried to save him, and the incalculable ways in which we all try — and fail — to protect ourselves and those we love most.

How did you handle writing about real people in your life?

I think nonfiction writers owe our “characters” the same kind of curiosity that fiction writers bring to their work. When writing about people we know, we need to shed what we think we know about them. Let them surprise us. I tried to do this by setting contradictory moments side by side: my mother’s medical expertise and tenderness next to her religious dogma; my father’s belief in human exceptionalism next to the inevitability of his early death; my past self next to my present. A good story resists reducing a person to a single moment. I didn’t want to explain anyone in my book as an example — of a psychological diagnosis or history or demographic. Besides, there are plenty of experts out there who offer those contexts. I was interested in exploring the knots of paradox we carry inside ourselves.

I showed an early version of the manuscript to my youngest sister, whose wise response is now in the epilogue. But in the end, I didn’t show the final manuscript to anyone besides my editor and to the person who is my first reader for everything. While I don’t think I’m in control of the narrative — readers will interpret it freely — I do think I should be the only one responsible for what’s in the book.

Your mother is such a complex character. How did you reconcile all the parts in your mind to then put them on the page?

By not reconciling any of it! She is a person of unresolved contradictions. That’s why she’s so compelling on the page — by turns infuriating, funny, off-putting, admirable, and sympathetic. The easier story would have been to focus on her follies — as some people do. Or that she was simply a great mom or brilliant veterinarian. The craft demanded that I combine particulars that created friction with another. Every sentence I wrote about her was like striking a match. The notion of resolving an issue before writing about it might work well for some, but it doesn’t work for me. If I tried to reach coherence before I started writing, I wouldn’t write. I want to lean into the strangeness and unknown, one sentence at a time. Instead of arriving at one interpretation, I arrived at multiple incompatible yet equally valid insights, like dapples of light that show in the dark simultaneously.

Did your memories open doors to more memories? Was there one in particular you’d like to share?

Your beautiful question shows you know how memory works. Sometimes people think one must have fully fleshed memories to write a memoir. But you only need one detail to begin — an image. Or a smell. These particulars ring down a resonating chain. For me, it was the sound of my father’s breath when he ran. I used to ride my bike next to him. I can still hear the phrase of his inhales and exhales. Now comes the crunch of gravel under his feet. Now the smell of his sweat. And here: the gentle slope of his forehead. The easy swing of his arms. Breath became a motif in the memoir — I held mine when I feared for his life. As my father’s body changed, so did the way he smelled when I breathed around him, and, of course, I was with him when he drew his last breath. My father felt closer in the six years of writing this book than in the previous 19 years of his absence. It was a surprise and a gift.

Although the book chronicles your girlhood, you do enter the narrative at times from the point-of-view of you as an adult. Was that a conscious decision?

The crucial tension in memoir is the one between the past and present. And I was most interested in those moments when my present self wanted something from the past that I couldn’t get. What did my younger self know that I no longer do? Where is my younger self amidst the vivid portraits of my mother and father? Despite all that I know now, there was a clarity my younger self had that I no longer have access to. Though I am in fact the person who had these experiences, my younger self often remains elusive as I attempt to remember. The past will not be smoothed over by my so-called wisdom now. Instead, I found myself humbled, bewildered, awed. I entered the narrative with my present P.O.V. when the narrative tension built toward an inevitable encounter between the present and past, like a clash between protagonist and antagonist.

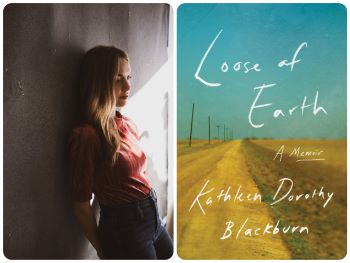

[Photo by Fox and Wilds Photography.]

Cathy Alter is a member of the Independent’s board of directors and the author, most recently, of CRUSH: Writers Reflect on Love, Longing, and the Power of Their First Celebrity Crush.