Books for times of bereavement.

A month after the death of my mother at the age of 94, I visited my daughter, Rozzie, and her partner, Olivier, who live in the French village of La Chapelle aux Naux. It lies in a floodplain on the Loire. As we walked beside the river, Rozzie explained that, over the centuries, the village has been submerged many times. Once, floodwaters carried off the church. The debate about where to rebuild became so bitter that some parishioners split off and converted to Protestantism.

“It sounds like a scene out of Barbara Comyns,” I said. I’d just discovered Comyns and was reading all her novels. Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead opens with a flooded village:

“The ducks swam through the drawing room windows. The weight of the water had forced the windows open; so the ducks swam in. Round the room they sailed quacking their approval; then sailed out again to explore the wonderful new world that had come in the night.”

The story takes a peculiar turn when villagers start dying off. You might call Comyns absurdist, but the book was inspired by a mass poisoning in 1951 in the French village of Pont-Saint-Esprit.

My mother would’ve loved it, and I wish I could have shared it with her. Even so, most of the time, I don’t feel sad about her. Mostly, I feel grateful for how she lived and what she gave us. Bereavement, I find, isn’t just about sadness. It’s about navigating a seismic shift in the landscape of your world.

Perhaps that’s why it’s comforting to read Comyns. She has such a talent for interweaving whimsy with misfortune and disaster. Her stories include abrupt shifts in fortune to which her characters must adjust. Their randomness reflects what bereavement teaches us about life.

As we walked along the river, thinking about the church that had been forever swept away, we were caught in a torrential downpour. Rozzie had warned us to bring waterproof footwear, but I guess we didn’t believe her. Our shoes took days to dry out.

On Saturday, Rozzie and Olivier threw a wonderful party. We sat around the garden table on rickety chairs, an eclectic group that included a strawberry farmer, a family who’d returned from rock climbing in Senegal, a bande desinnée author, and a shepherd who lives part time by himself in the mountains. The sun shone all afternoon.

But the next day, clouds rolled in. We’d just set the table for lunch in the garden when we had to dash inside with our plates and glasses and take the washing down from the line. Bereavement is like this, too. It engulfs you when you’re least prepared.

I lay on the bed, listening to the rain, reading Our Spoons Came from Woolworths, my favorite Comyns novel so far. Narrator Sophia Fairclough marries a young painter. There’s a fairytale quality to their lives despite their grueling poverty. Sophia tells us:

“Before our marriage Charles used to paint and draw me quite a lot, but now we were living together I had to pose in every imaginable position. In the middle of washing the supper things, Charles would say ‘don’t move’ and I would have to keep quite still, with my hands in the water, until he finished drawing me, or I might be preparing the supper and everything would get all held up. He painted me in the bath once and I have never been so clean before or since. Sometimes when I woke in the morning there would be Charles painting me asleep. That was the most comfortable way to be painted, but it made me late for work.”

But soon, artistic struggle, hunger, and a difficult childbirth take their toll. This is followed by betrayal, illness, and death. The most insidious trial is the invisibility Sophia suffers when she gives up her dreams for a job that pays the bills.

The novel is painfully sad, but the narrator’s perspective makes it somehow bearable. The story is told from a distance, and Comyns hardly ever uses dialogue. Her attention to eccentric detail provides the story richness and complexity.

I have another reading suggestion for times of bereavement. A member of my book club who’d suffered a family loss found that Stéphane Heuet’s bande desinnée adaptation of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time: Swann’s Way was at times his only pleasure. It’s available in English translation by Arthur Goldhammer. My friend found it enchanting. I think that’s down to the whimsical approach and immersive quality of bande desinnée.

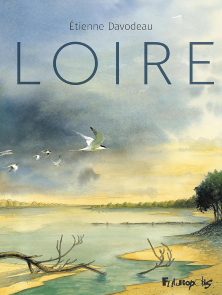

Olivier has a bande desinnée bookstore in Tours, which I wrote about in an earlier column. This visit, I purchased a copy of Loire by Étienne Davodeau and found that its subject was loss. In it, when Louis receives an invitation from Agathe, a woman he once loved, he is touched and intrigued. It’s been some time. But when he arrives in the Loire, he finds that she has died. Other loved ones have also been summoned, and it turns into a memorial gathering. They must come to terms with the loss of Agathe as well as with the ways she still may be with them.

Davodeau’s soft yellow ochres and subtle shades of blue capture the quality of the Loire and its environs. His drawings are atmospheric and honest. The Loire is rough. Its presence and unpredictability cannot be ignored. The Loire is a fleuve in French, by the way, not a riviere, because it flows to the sea.

The last several pages have no text. The drawings depict different tempos and moods as the river changes with the weather. Loire is full of whimsy and joy. Then there are outbursts that seem to come from nowhere. Davodeau’s final words suggest how we can navigate these tempests: “Je voudrais penser comme un fleuve,” he writes. I would like to think like a river.

Amanda Holmes Duffy is a columnist and poetry editor for the Independent and the voice of “Read Me a Poem,” a podcast of the American Scholar.