A 2022 biography splendidly captures the enigmatic Charlie Watts.

A founding member of the Rolling Stones and the band’s bedrock drummer for nearly six decades, Charlie Watts died at age 80 in August 2021. His death prompted many interviews with his bandmates and other rock luminaries, obituaries in the music and general press, and marathons of Stones music on classic-rock stations. Soon after, in 2022, Paul Sexton published Charlie’s Good Tonight: The Life, the Times, and the Rolling Stones, an extension of “the global cascade of affection,” to quote the author, surging over the late musician. Though two years old, Charlie’s Good Tonight warrants another look.

Sexton, a veteran rock journalist and documentarian, had produced shows on the Stones for BBC Radio 2 before he undertook his “fully authorized and official biography” of Watts. Sexton evidently knew Watts well and enjoyed full access to him, his bandmates, and his family and close friends. A thorough researcher, Sexton also interviewed any number of British and American musicians and consulted untold published interviews and articles. He has used all these sources to create a tasteful biography that is also a fine tribute to a friend.

Watts studied art in the 1950s and worked as a graphic artist while establishing himself as a musician in the early 1960s. Over the decades, he played an increasingly active role in the design of Stones album jackets and, more ambitiously, in the staging of their spectacular stadium concerts. He and his wife, Shirley, by all accounts, shared highly evolved aesthetic sensibilities and impeccable taste. Watts drew constantly, including his widely reported habit, confirmed by Sexton, of retiring after performances and making pencil sketches of “the bed in every hotel room” he stayed in — an interminable series that he then collected in books.

Watts’ métier and main passion, of course, was music, particularly jazz. As an emerging young musician, he revered Max Roach, Chico Hamilton, Phil Seaman, and comparably elite jazz drummers. Like other British jazzmen of his generation who transitioned to rock — notably Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce — Watts passed through Alexis Korner’s band Blues Incorporated. Baker recommended Watts to Brian Jones, and the nascent Stones recruited him. (In turn, Watts recommended Baker to Korner.) During his career with the Stones, Watts developed successful jazz side projects, such as the Charlie Watts Orchestra, a “big band” tentet, and the Charlie Watts Quintet, a smaller and more refined group.

When Watts first joined the Stones, he knew little about rock ‘n’ roll or blues, leading Keith Richards to note in his diary: “Charlie swings very nicely but can’t rock.” Using the individual Stones’ unusual record collections, Watts studied Chicago blues, schooling himself on legends like Jimmy Reed, a particular favorite of his new bandmates. His drumming style was understated. He considered the drummer’s job to be setting the beat and keeping time; he would not do solos, and he preferred a jazz drummer’s modest kit to the typical rocker’s extravagant setup. According to his lifelong friend, the double-bass player Dave Green, “We just wanted to sit there and swing for the band.”

Ironically, Sexton faced the challenge that Henry James called writing a biography without a true biographical subject: a biography of someone, that is, with neither great adventures nor great intellectual achievements. Watts had ready access to all the adventures, or misadventures, available to celebrated rock musicians on tour, yet he shunned them. He also amassed formidable artistic achievements and had a keen intelligence, but he deprecated the former and downplayed the latter. He labored, in other words, to make his uncommon life appear common and his considerable talents ordinary, leaving his biographer to write “a gentle tale of a life well lived” and immune to controversy.

That tale portrays an idiosyncratic man universally liked, respected, and admired, a man whose character and habits are recalled with uncanny unanimity by family and friends. Devoted to his wife, daughter, and granddaughter, Watts guarded his privacy intensely. He hated touring and show business, preferring life in the bucolic setting of his 600-acre horse farm. He was passionate about jazz and art but also about soccer and, particularly, cricket. He was notoriously laconic and reserved but also had a sharp sense of humor and a marked generosity. He had “pristine manners” redolent of an earlier era. He was, in fellow Stone Ronnie Wood’s assessment, “a perfect English gentleman.”

Two of Watts’ more pronounced habits have their own chapters in Charlie’s Good Tonight. One, Watts was an obsessive collector of antique cars, military and cricket memorabilia, signed modern first editions, vintage classical and jazz recordings, drum sets played by legendary drummers, and museum-quality clothes worn by such figures as the duke of Windsor. Two, He was an impeccable dresser who fancied bespoke suits and jackets from Savile Row, handmade custom shoes from London’s most venerable purveyor, and, onstage, T-shirts and slacks identically tailored if varied in color, the former designed with “an extra side panel.” In Sexton’s nice allusion, Watts was “a man of wealth and taste.”

Sexton approached the challenge posed by Watts’ life with two smart maneuvers. First, he kept the book slim and brisk. It numbers over 350 pages, but they are set in a large font with considerable air. And second, he gave the narrative a noticeably traditional shape. Resorting neither to dislocated chronology nor to other aesthetic gimmickry, it employs, as its subtitle signals, the conventions of the genre exemplified in the famous Victorian series English Men of Letters. In short, Sexton’s volume mirrors both the sensibility and the style of its biographical subject.

More important, Sexton has built his picture of Watts deftly and tactfully on quotations. This not only reflects the essence of portraiture — the depiction of external surfaces to suggest internal depth — but also employs the only strategy possible for a very private and guarded subject. Watts and his wife observed strict boundaries in interviews, as Watts’ bandmates and friends did with Sexton. Charlie’s Good Tonight might well have ended like “Citizen Kane” — that masterpiece of portraiture crafted from the views of others — with a shot of a “No Trespassing” sign.

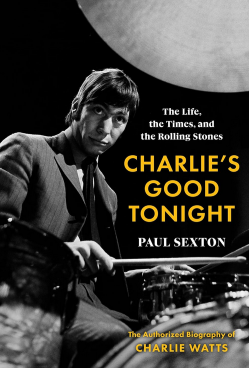

Sexton neatly encapsulates his story’s narrative arc in two photographs of Watts that fill the front and rear panels of the book’s dustjacket. An informal shot on the front depicts a youngish drummer playing intensely at his kit, staring from heavily shadowed eyes and face. He looks decidedly thuggish. A studio portrait on the rear displays an older gentleman artfully and languidly posed, his refined profile highlighted, gazing with studied diffidence. Oozing elegance, he could be one of the royals, aristocrats, or literati portrayed by Cecil Beaton a century ago.

The Stones would not survive the loss of Mick Jagger or Richards, Watts once told an interviewer, but could play on, if need be, with replacements for Wood or himself. He was almost right. Watts played the pre-pandemic leg of the band’s No Filter tour in 2019 and recorded two cuts on “Hackney Diamonds,” released in 2023. But the Stones made the post-covid leg of No Filter in 2021, the Sixty tour in 2022, and the Hackney Diamonds tour of 2024 with veteran musician Steve Jordan, anointed by Watts as his replacement, on drums. Jordan has succeeded Watts admirably, but nobody, in the end, can “replace” him.

Ginger Baker once said that John Bonham, Led Zeppelin’s drummer, “had technique, but he couldn’t swing a sack of shit.” No one, least of all Baker, would have said that about Watts. In fact, many musicians cited by Sexton said just the opposite. As Pete Townshend of the Who put it, “Not a rock drummer, a jazz drummer really, and that’s why the Stones swung like the Basie band!!” It’s a fitting epigraph for the Rolling Stones and epitaph for the incomparable Charlie Watts.

Charles Caramello is a professor emeritus of English at the University of Maryland and John H. Daniels Fellow at the National Sporting Library and Museum in Middleburg, VA.

_80_120.png)

_80_125.png)