New collections to make life more lyrical.

When I think of the waters of Uruguay, I think of the beautiful beaches and rocky pools of Punte del Este and the immense Rio de la Plata, which divides Uruguay from Argentina.

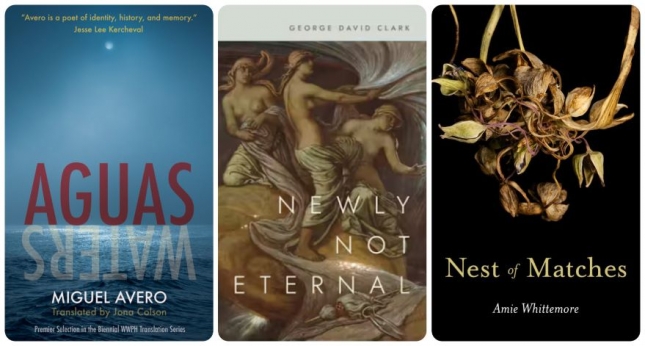

Having lived four years in Argentina, I was curious to read Aguas/Waters (Washington Writers Publishing House) by Miguel Avero. It draws from two previous collections and includes English translations by Jona Colson on facing pages.

Avero was born in Montevideo in 1984, the last year of Uruguay’s military dictatorship. During that brutal regime, which began in 1973, the free press was shut down and one in 50 people was arrested. Hundreds were tortured and “disappeared.” But, at least overtly, this is not Avero’s subject. He writes:

The rain foreshadowed the future

But we were childrenWith no need to remember

In the introduction, Colson characterizes Avero as carrying on a Latin-American tradition with poems that sometimes reflect “magical realism, where extraordinary events are accepted as common and not explained.” This, I think, is a little misleading. Yes, his imagery is often surreal, and he hints at an indistinct and troubled past:

The ocean withdrew,

all resurfaced with its most violent face.

with its face of nothing,

with its stillness of death.

But rather than addressing society’s darkness with the subversion of magical realism, Avero is more interested in psychological undercurrents. His poems are often contemplative and in a register of wistful reflection. He writes:

What in that time

Took root

Remains in an underworld

Of impenetrability

It is misty, fogged

Elsewhere, he acknowledges:

The pages are not forgotten.

They fog up.

There are storm clouds, sorrows, sheets of rain and fog. Also, shadows, a stark sun that umbrellas can’t protect him from, the abuses of silence, the futility of speech.

Colson’s translations are plainspoken and sincere, although a few subtle choices may sometimes alter meaning. For example, in “Hegemony,” he translates “El cielo nos observa/como a un desnudo abismo” as “the sky watches us/like a naked abyss.” An equally accurate reading might be, “heaven sees us as a naked abyss.”

He translates the next line, “el agua estalece su hegemonia celeste,” as “the water establishes its celestial hegemony.” Celestial is the same word in English and Spanish, but Avero’s word here was celeste, meaning “sky blue” (blanco y celeste are the colors of the Argentine flag). I see “hegemony” with its negative connotation — as related to political or economic dominance. Maybe I’m over-analyzing, but as I read and reread this collection, I couldn’t help flashing on the bodies of the “disappeared,” which were dropped into Rio de la Plata from “death flights.” All of which made me wonder if Aguas might not be more subversive than it appears.

And consider these lines from Avero’s title poem:

Agua en la tinta de los versos

Que no se escribiran nunca.Water in the ink of the verses

That will never be written.

In the Spanish verse, the word nunca (never) comes at the end of the line, stressing its import and hinting at an active refusal to write certain verses. They may be too painful to commit to paper. Were Avero to write more directly and specifically about Uruguay, he’d have some dark stairs to go down. But throughout, and particularly in this moving couplet, I sensed the gravitational pull of those unwritten verses.

*****

The cover of George David Clark’s Newly Not Eternal (LSU Press) is a painting by Elihu Vedder, “The Fates Gathering in the Stars.” This collection, centered on loss and the redemptive power of faith, begins with an epigraph from Ecclesiastes, “I have seen the burden God has laid on the human race. He has made everything beautiful in its time.”

In the opening lines of “The First Supper,” a dying infant nurses at his mother’s breast:

Newly not eternal,

newly partly

past, he’s here by way

of forty weeks

inside another volatile

physique.

He’s purple, then he quickly

pinks and hardly

breathes before we see

he’s breathing fine.

It’s only seconds

till he’s at her breast —

the sweet colostrum

like a spurt of fresh

infinity injected

into time.

The interchange between mother and child and the shifts among apprehension, hope, mortality, and immortality are conveyed with such delicacy and skill in these lines. He achieves the same balance in his modified crown of sonnets dedicated to the lost infant. In one, “Ultrasound: Your Urn,” a surviving child thrives alongside the enormous hole left by his missing twin. Here’s an excerpt:

The crumpled books

and cracker crumbs are proofhe’s loose...disordered

blocks, a toppled chair...Some days he’s absolutely

everywhereuntil I wish him gone,

to tell the truth.Not you. You stay

exactly as you’re left:the tame and quiet twin,

the easy one,the boy who never

makes a mess, the sonwhose whispered name

will be our shibboleth

If you thought devices like meter and rhyme were restrictive or outmoded, think again. The constraints they impose heighten rather than diminish the emotional intensity of these poems. John Donne is looking down with approval.

But Clark also brings the sonnet into the 21st century by breaking lines of iambic pentameter into couplets, so that the verses move freely down the page with plenty of breathing room.

Many of his poems have titles with Christian allusions, and he’s as open about his faith as he is about his suffering. Faith for him is both solace and struggle. To paraphrase his epigraph from Ecclesiastes, a painful burden is placed on the spirit. But this collection is a testament to the human struggle and the transcendent power of poetry.

*****

Lunar cycles, the cycles of love and longing, the dreamworld, and the fierce beauty of the natural world are some of the themes in Amie Whittemore’s new collection, Nest of Matches (Autumn House Press). Many poems here were evidently composed during covid, and they remind me how we were forced during that time to slow down and live more quietly. In spite of its horrors, the pandemic offered some of us time to reflect, to appreciate nature, to reassess our values, to mourn what we had lost. Above all, it forced us to grow.

All this is reflected in Whittemore’s poems. In 2020, she assigned herself the task of writing about each full moon as it came up and learning the Native American and European names for them. There’s a pink moon, a strawberry moon, a cold moon, a harvest moon, and each moon poem marks a different time of year, a different season, and a different mood. “Wolf Moon” begins:

It hung like a blank

eye last night over

my walk, pale

as its other names —

Ice moon, old moon

— dragging the past

behind it, a heavy sack

Also included here is a series of queer love poems with variations on the title “Another Queer Love Poem that Fails.” They chronicle loves past, loves unrequited, loves that were enough, and loves that failed. One of my favorites is “Another Queer Pastoral That Isn’t a Time Machine,” although it is a time machine in that it puts us right in the middle of the moment. She writes:

she couldn’t trust we sang that night

in the hot tub the stars only looking like an audienceher voice a vase mine the wrong flowers

can you ever find your past like a coinin a pocket can you go to the tall grass

and not think of ticks is that freedom gone

Then there are achingly painful poems, such as “The Problem of Being Good,” lamenting the breakup of a marriage. Notice how the self-reproach comes out breathlessly, all in one go. It reads, in part:

I did not think that good sex for one person

could be bad sex for the other if it was

consensual, particularly if it was in my control.I understood afterward how you could become

a homonym of yourself and begin to live there.

I thought when I got divorced my parentswould not disown me, but would despair

and judge me as fickle and unworthy

of grand gestures and pretty dresses forever.

The voice in these poems is authentic and unguarded, which is why I read straight through with pure enjoyment. So no, this is not a collection of queer love poems that fail. It’s a fresh and beautiful collection that celebrates queerness while also going beyond it to become a work for everyone who’s ever loved and doubted or loved and failed.

Amanda Holmes Duffy is a columnist and poetry editor for the Independent and the voice of “Read Me a Poem,” a podcast of the American Scholar.