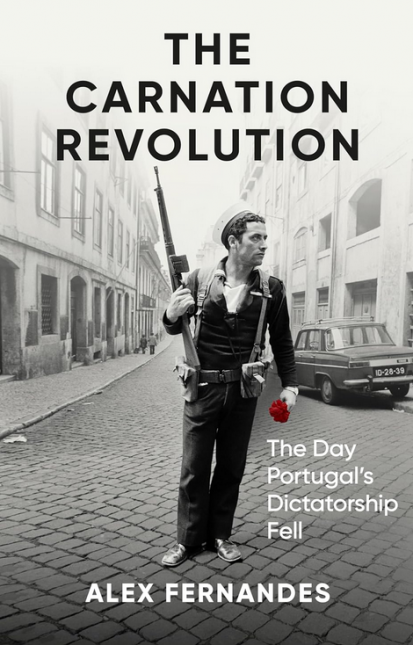

The Carnation Revolution: The Day Portugal’s Dictatorship Fell

- By Alex Fernandes

- Oneworld Publications

- 400 pp.

- Reviewed by Andrew M. Mayer

- July 4, 2024

An outstanding account of the Estado Novo’s demise.

Author Alex Fernandes has written in The Carnation Revolution: The Day Portugal’s Dictatorship Fell a definitive account of the upheaval his country underwent on April 25, 1974. To fully understand the 50-year-old event, he delves into Portuguese history from the time of Henry the Navigator (1460), an era when the slave-trading Portugal and Spain — long before England, France, Holland, and Germany — were the primary builders of empire in Africa, India, and the Pacific.

Both nations also brought slaves to the New World in the 15th and 16th centuries, their commercial boundaries broadly set by a series of papal bulls. Among its conquests, Portugal took control of Brazil and established the colony of Goa in India; it would rule over both for hundreds of years. While the Portuguese monarchy endured beyond the eventual end of slavery in Brazil (in 1889), it was abruptly terminated in 1908 with the dual assassinations in Lisbon of King Carlos I and his heir-apparent, Luís Filipe.

What followed was a chaotic attempt at governing during the First Portuguese Republic (1910-1926), which saw eight presidents and 45 governments. A military coup unfolded in 1926, and the mastermind behind it, António de Oliveira Salazar, would become Portugal’s leader from 1927 to 1969, a period christened the Estado Novo (“new state”). During this time, the country saw sporadic yet nearly continuous rebellions in the trade unions, academia, and, above all, the armed forces. All were unsuccessful. Portugal was neutral in World War II and, during the Cold War, turned toward the West while battling domestic communist and socialist elements hoping to remake the government.

The most serious threat to the Estado Novo came vis-à-vis Portugal’s longstanding efforts to maintain colonial control over the remnants of its empire, especially Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and Angola. As the Portuguese military struggled to quell uprisings by far-flung terrorist groups (such as FRELIMO in Mozambique and MPLA in Angola), members of the armed forces began to make secret inquiries about how to moderate — or possibly overthrow — the dictatorial Estado Novo.

In February and March 1974, a group of officers from all branches of Portugal’s military met clandestinely in private houses around Lisbon to prepare for revolt, forming a group known as the Armed Forces Movement (MFA). While doing so, they had to avoid the eyes of the country’s secret police (PIDE), which dealt especially brutally with radicals and disloyal soldiers.

A month later, on April 25th, during what became known as the Carnation Revolution, the MFA moved simultaneously on the presidential palace and PIDE headquarters in a largely bloodless coup. They called on General António de Spínola to arrest Salazar’s successor, Marcelo Caetano, as well as the vice president and numerous intelligence personnel. Spínola was then put in charge of the new provisional government.

Over the next year, however, there was a constant fight for power — nearly a civil war — between the centrist military and elements of the far right and far left. Finally, the communists were defeated on November 25, 1975; a new constitution was approved in 1976. Since then, despite having six provisional governments, Portugal has operated as something of a democratic republic and has avoided further overthrow attempts. (Ironically, Spínola attempted a siege of his own in late 1975 and was forced to flee to Spain.)

Along with thoroughly chronicling the events of the Carnation Revolution, Fernandes dives deep into other conflicts Portugal endured in the post-WWII era, including the unsuccessful presidential bid of opposition candidate Humberto Delgado in 1958. It was the dramatic failure of General Delgado’s campaign that first began to stir the populace against Salazar’s Estado Novo and toward revolution.

What is particularly unusual about this book is that, in order to effectively explain the events of a single day in 1974, the author first had to explain nearly 500 years of Portuguese history encompassing empire, slavery, monarchy, economics, geography, and evolving social mores. By doing just that in such a spectacular fashion, Fernandes has given readers an extraordinary gift.

Andrew M. Mayer is professor emeritus of humanities and history at the College of Staten Island/CUNY.