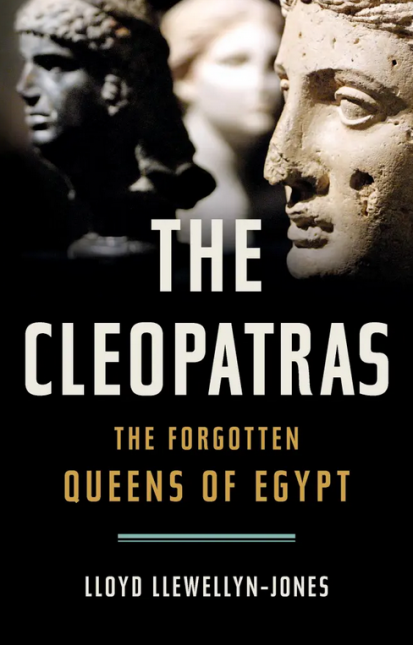

The Cleopatras: The Forgotten Queens of Egypt

- By Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones

- Basic Books

- 384 pp.

- Reviewed by Rose Rankin

- June 6, 2024

A riveting look at the women behind antiquity’s most recognizable name.

The name Cleopatra immediately conjures an indelible image — the raven-haired beauty, the sultry temptress portrayed in thousands of representations, from Shakespeare to Elizabeth Taylor to Netflix shows being produced today.

Indeed, Cleopatra is one of the most famous women the world has ever known, but this outsized reputation has obscured the fact that the Cleopatra was actually Cleopatra VII, the last in a long line of Egyptian queens who shared not just her name but also her political acumen and colorful story. Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones takes a major step toward rectifying this oversight with The Cleopatras: The Forgotten Queens of Egypt, which digs deep into the historical record to bring this dynasty to life in an easily readable, powerful narrative that makes “Game of Thrones” seem like child’s play.

Llewellyn-Jones begins with the world Alexander the Great left behind after his untimely death in 323 BCE. The eastern Mediterranean and Middle East were divided among Alexander’s generals, with the Greek general Ptolemy seizing control of the already-ancient land of Egypt. His family and the Seleucids, another family of post-Alexander rulers based in what is now Syria, were the protagonists in an ongoing series of wars and alliances that lasted until the Romans took control of Egypt in 30 BCE.

The first Cleopatra, Cleopatra Syra, was a Seleucid princess who married into the Ptolemy family (the last non-Ptolemy to do so). The Ptolemies codified incestuous marriage as part of their dynasty to a degree that would, to return to our “Game of Thrones” reference, make any Lannister or Targaryen blush.

Cleopatra Syra arranged for her son and daughter, Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II, to wed each other, and following that marriage, Cleopatra II married her other brother, Ptolemy VIII. The incestuous relationships got even stranger when Ptolemy VIII, while still married to his sister, took her daughter, his own niece, as his second wife, making her Cleopatra III.

The fact that all the kings and queens were named Ptolemy and Cleopatra is confusing, but Llewellyn-Jones does well to incorporate family trees and who-married-whom/who-murdered-whom reminders throughout the book so readers can keep the dizzying dynastic intrigue clear in their minds.

He also doesn’t fixate on the prurient aspects of these marriages, instead examining them in a sociopolitical context wherein pharaohs presented themselves as gods or demigods. As the nearest thing to those Egyptian and Greek deities, all of whom married their siblings in mythology, the Ptolemies were using every method available to appear as legitimate royalty, when in fact they were outsiders who’d ruled for barely a hundred years.

The murders and marriages continued through the second century BCE, even when some Cleopatras married outside the family. Two daughters of Cleopatra III eventually wed Seleucid kings caught in their own civil war, and one sister had the other brutally executed. Cleopatra III herself was murdered by her son Ptolemy X — a violent ending caused by the Ptolemies’ custom of having multiple generations rule as co-monarchs, a perfect storm of power struggles that tore the dynasty apart.

It was only two generations later that Cleopatra VII ascended the throne and allied herself first with Julius Caesar and then with Marc Antony in attempts to sideline her brothers (both of whom she married; the second one she later had murdered). By this time, Rome was the true power broker of the region, and after Cleopatra VII and Antony’s troops were defeated in 30 BCE, Egypt fell under Rome’s dominion. The Ptolemaic dynasty ended with Cleopatra VII’s subsequent suicide.

In retelling this family drama, Llewellyn-Jones makes excellent use of the sources available to him. Concrete declarations about ancient history are always fraught, and he acknowledges what we can’t know but cites the material culture of coins, steles, and artwork to explain what we can. Egyptian history has fortunately been preserved via written documentation, yet the author is wise to note that accounts of the Cleopatras often reflect the misogyny of ancient writers and modern historians alike.

Unfortunately, his emphasis on filial melodrama doesn’t reveal much about how these extraordinary women actually governed. We’re told some were loved and others were hated, but we aren’t told why. Did they, say, enact punitive taxes? And did they build anything beyond renovating the occasional temple? For all their marriages and machinations vis-à-vis the throne, we learn precious little about what they did day-to-day.

This is likely evidence of the historical record’s lack of, well, evidence. Again, such is the challenge with ancient history. No matter. The stunning tales of battle, poisonings, unions, and family strife assembled here are enough to overcome these omissions and keep the reader glued to the page. The Cleopatras is an excellent reminder that the most exciting stories are the true ones, and that the book is always better than the movie(s).

Rose Rankin is a freelance writer from Chicago. She focuses on history, science, and gender issues, in particular women’s literary history.

_80_124.png)