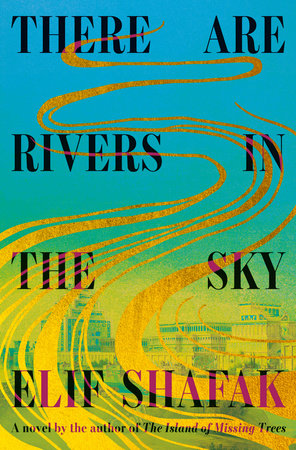

There Are Rivers in the Sky

- By Elif Shafak

- Knopf

- 464 pp.

- Reviewed by Martha Anne Toll

- August 28, 2024

A mesmerizing tale coursing with wisdom and water.

There Are Rivers in the Sky is the first Elif Shafak novel I’ve read, but it won’t be the last. Shafak, a Turkish British writer, is prolific, and her latest tale jumps off from a single raindrop as witness and storyteller through the ages. I was immersed in it in many ways.

In a prologue, we meet King Ashurbanipal (mid-600s BCE), “leader of the wealthiest empire in the world, last of the great rulers of the kingdom of Assyria,” and the calculating, bloodthirsty creator of one of the greatest libraries humans have ever known. He rules Ninevah, on the banks of a tributary of the Tigris River called Khosr, and wanders through his legendary library “lined with floor-to-ceiling shelves that hold thousands of clay tablets.” His favorite volume is the ancient flood myth The Epic of Gilgamesh.

As the king luxuriates over the box containing this story, his mentor is dragged in enchained, begging the king to save his starving people and chastising him for his cruelty. The mentor provides one last lesson before being executed. He tells Ashurbanipal that Gilgamesh traveled to the ends of the earth but failed to become immortal. “The only way to be remembered is to leave a good story,” he warns. “My king, why is it that you chose to make your story such a heartless one?”

The prologue ends with an ominous warning:

“Water remembers. It is humans who forget.”

Immediately following is a depiction of a water molecule, suggesting that its three atoms (H, H, and O) represent the novel’s three protagonists. Arthur is a 19th-century British linguist. Narin is a modern-day Turkish Yazidi girl being taken by her grandmother to Iraq — through land controlled by ISIS — to receive a blessing to heal Narin’s encroaching deafness. And Zaleekah, a contemporary British hydrologist, is suicidally depressed after her recent divorce and living on the Thames in a houseboat.

Water, in its many formations, drives the action and serves as a metaphor. “Rivers are especially good at remembering,” Shafak reiterates. The four primary sections of the book — Mysteries of Water, Restless Rivers, Memories of Water, and Flood — suggest both plot and the key role water plays.

Of the main characters, I found Arthur most compelling because his story contains the most detail, as if Shafak intended him to anchor the novel. Born in 1840 London, he is the son of an alcoholic father and a mentally ill mother. He’s raised in abject poverty and suffers from chaos and illness as cholera and other diseases make their way through the city’s slums. Never veering far from her theme, Shafak detours to tell readers the story of the discovery that cholera is waterborne.

Arthur cannot receive the schooling he craves but possesses a superlative memory. He’s fascinated by books and, above all, by Ninevah. Through happenstance and grit, he finds work at a printer’s office, which ultimately leads him to the British Museum. With his gift for decoding ancient stone tablets, he eventually makes his way to the Middle East to study them. (I’ve read that Arthur is based on real-life British Assyriologist George Smith [1840-1876], and many particulars of Shafak’s Arthur hew to those of Smith.)

Shafak has adopted W.G. Sebald’s style of placing choice photographs throughout her narrative. These photos illustrate ancient artifacts and overland explorers, giving the book its lovely gauzy quality of hovering in a multiverse that spans fiction and nonfiction. I quickly sank into Shafak’s lush language and felt connected to her characters. Though spinning a yarn, she stays close to the political morass of the present. Iraq figures prominently both as a home to vast civilizations and as a cauldron of ongoing conflict. Narin’s father reminds her that whether they are categorized as Kurdish or Yaziki, “We are the memory tribe.”

Zaleekah’s is a family of immigrants to England, albeit well-educated and cosmopolitan ones. She has fallen in love with a woman, and her journey takes her back to her roots, where she must delve into the meaning of her family’s past. As she moves to embrace her lifestyle and share it with her relatives, readers are exposed to the nuances of generational and cultural differences surrounding sexual identity.

I was impressed with the way Shafak has crafted an epic out of an epic. The magic of this novel lies in her skill at captivating readers with terrific storytelling while reminding us that human arrogance and frailty are too often the engines that drive history. The same creatures who can create great art and reach the pinnacle of civilization have an equally powerful — and terrifying — capacity to destroy it all.

Martha Anne Toll is a literary and cultural critic and a novelist. Her prizewinning debut novel, Three Muses, was published in 2022. Her second novel, Duet for One, is forthcoming in early 2025.