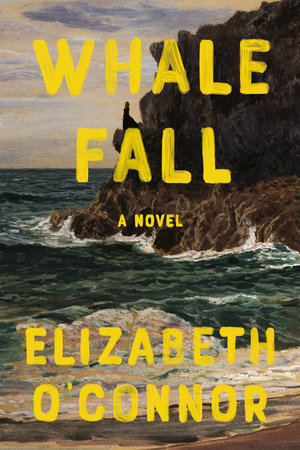

Whale Fall: A Novel

- By Elizabeth O’Connor

- Pantheon

- 224 pp.

- Reviewed by Carrie Callaghan

- July 9, 2024

A restrained, beautiful story of an island nearly smothered by isolation.

On this remote outpost in the British Isles, life and death walk constantly hand-in-hand. An island year, novelist Elizabeth O’Connor tells us in her debut, Whale Fall, is marked by the life cycle of birds and the rotation of sheep who have grazed the plants to nothingness. And more than anything, there are the never-ending waves, which take a sacrificed sheep thrown into the sea and push it back to shore for the birds to eat.

Manod, born in 1920, is 18 during the book’s particular island year. She is smart and full of dreams but weighted by a melancholy that we suspect has to do with her mother’s disappearance some time before. Or perhaps the weight pulling at Manod’s ankles like sucking sand is the island itself, its increasingly claustrophobic and difficult life. There’s one boy her age, Llew, whom she allows to have sex with her, though Manod seems mostly bored by the whole enterprise. She refuses to marry him.

But two heralds arrive: a dead whale, washed up on first one beach and then another, and a boat carrying two English researchers. Manod’s father, who often calls her by the dog’s name, worries that the whale is bad luck. When Manod goes to see it, the brown surf and its froth remind her of the sheep heads her father boils on the stove, “fleece around the rim of the pan.” The carcass seems almost pathetic, vulnerable, “gigantic and curled against itself.” There is nothing glamorous about death in Manod’s world, nothing glamorous at all except the prospect of leaving. Which the two English people offer, like a scent on the wind.

Manod is fascinated by Edward and Joan, searching for the couple’s footsteps in the mud and speculating about them with her odd younger sister, Llinos. Within their footprints in the sand, Manod sees the dune grass dying, “letting its seeds fall into each print’s markings.” Life renews itself in death’s English tread. Manod dreams of being a teacher on the mainland, so when Joan asks her to translate interviews with the islanders for them, she eagerly accepts.

But Manod is also perceptive about the ways in which the researchers, there to document island life, underestimate her and misrepresent her home. Joan condescends, telling Manod about the novel Treasure Island, which Manod has already read, and Edward snaps at Manod when she explains that the post comes only every month or so. But still, she is seduced by their stories of mainland England, reassured by their promises.

“‘It’s truly amazing,’ Joan said. ‘The way you live.’”

But to Manod, it’s not amazing. Life is drudgery and death and snatches of beauty. She crafts delicate, fantastical embroideries and dreams of a better life, even while fellow islanders who visit the mainland tell dismaying stories about a lack of work and an impending war.

This slim novel passes quickly, like flashes of a bird seen between the blades of marsh grasses. Manod is restrained, letting the tales and images around her speak for her, so her inner life feels both removed and expansive. As the whale slowly deteriorates on the shore, eaten by birds and ultimately hacked apart by humans, Manod tries to find her own footing in life. She is coming of age in a place that has little sympathy for dreams, and certainly not those of women.

Early on, Manod thinks of a story about the island’s history, how there was once a king, but following his death, none of the other men, too busy trying to survive, wanted the job. Her mother told her that no one asked the women.

O’Connor infuses the story with both a sense of claustrophobia and the wide horizons of a land adrift in nature. People from crowded places seem to have no shortage of curiosity about isolated ones and the people who live in them, sparking novels like Emma Donoghue’s Haven and movies like “The Banshees of Inisherin.” Perhaps the covid-19 pandemic heightened this curiosity. O’Connor is both curious and perceptive, approaching her fictional island with a sensitivity that honors the challenges its residents face and the complicated love fostered by being from somewhere.

The quiet restraint and patchwork assembly with which she builds the narrative might baffle some readers. But for anyone who loves the simple poetry of yearning and the unknowable relationship between life and death, this book will come as a delightful gift.

Carrie Callaghan is the author of the historical novels A Light of Her Own and Salt the Snow (Amberjack/CRP). She lives in Maryland with her family and four ridiculous cats.