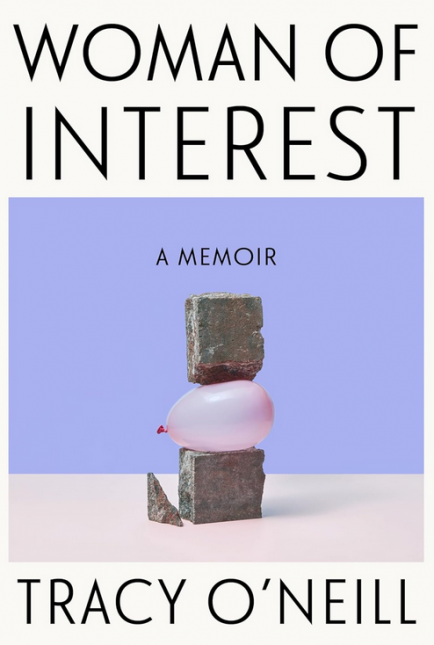

Woman of Interest: A Memoir

- By Tracy O’Neill

- HarperOne

- 288 pp.

- Reviewed by Alice Stephens

- July 11, 2024

A Korean adoptee is a detective on the case of her own origin story.

Whether we realize it or not, we’re all a product of stories. To the victor go the spoils, and here in America, that means an inculcation in tales of George Washington’s incorrigible honesty, Manifest Destiny, and national exceptionalism. Marginalized groups bear the brunt of these fabrications, fashioned to legitimize the seizure of land from the continent’s original inhabitants, the enslavement of human beings, the expansion of empire, and many other actions that resulted in egregious human-rights violations.

For adoptees who’ve come into consciousness, the power of narrative is a preoccupying theme. Our lives are shaped by the paperwork that holds clues to our origins, the stories our adoptive families tell us about our arrival and role in our families, and the popular conception of adoption that the public holds so dear. We find absolution in shaping our own narratives, and for many, that starts with a search for birth family.

Korean adoptee Tracy O’Neill has long been invested in the power of stories, making her living as a writer. During the 2020 covid lockdown, she “surrendered to obsession with a woman” and began to search for her Korean birth mother, chronicling her story in Woman of Interest.

When seeking birth family, adoptees must become detectives of their own lives, and O’Neill begins the memoir like a noir paperback, with quippy wordplay, a tough insouciance, and a hardboiled sensibility:

“This is where I confess that when I began my investigation, the case had been cold over thirty years. And you can live with a cold case. You do. The coldness of a case is how it is. Solving is the aberration, and I’d copped no novel leads.”

O’Neill finds Joe Adams, a private eye with a long résumé that includes working with the CIA in Central America under Oliver North and experience in South Korea. Although, as an agent of empire, Adams is more Tom Clancy than Raymond Chandler, the author sees in him the perfect partner to track down her birth mother. “I’d tried the conventional wisdom on searches,” she writes, “and all that got me was the inducement of organizations, agencies, and other PIs to call my case dead on arrival. With Joe, the case lived.”

She starts the mission with some embarrassment; all her life, she’d denied needing any maternal figure other than her adoptive mother. Raised in a white, working-class New England family, the author felt it her duty to be the daughter to only one mother, the one who plunked down $5,300 to bring her to America. But O’Neill had recently broken up with her long-term boyfriend and moved to Poughkeepsie, New York, writing, “I’d lost control of the story of my life.” Uncovering her origins is a way to claim it back.

Furthering the sense of mystery and danger, there are intimations of malfeasance at Eastern Social Welfare Society and Love the Children, O’Neill’s respective Korean and American adoption agencies. “Joe had heard from an FBI friend that there’d been some funny business involving Korean child imports around the time I’d been adopted.” Another FBI friend (or the same one?) cautions “that investigating Eastern was ‘a bag of worms.’” When O’Neill tracks down a social worker from Love the Children, she is warned, “[Y]ou might not like what you find out.”

Nevertheless, she persists, and without the assistance of Joe locates a relative the way most adoptees have, through DNA. He tells her that her mother’s name is one syllable off from what’s recorded on her adoption papers (which, coincidentally or not, was also the case for me). Other discrepancies arise: After describing her mother as a good woman, this relative says, “Your mom’s personality is not that great.” He intimates she has an issue with fidelity, as each of her four children has a different father; is a bad mother to her other daughter; can’t be trusted with money; can’t be trusted at all.

When the author learns that her birth mother hasn’t been told of her existence, she flies to South Korea, where she meets biological relatives for the first time. Communicating mainly through translation apps, she feels at a disadvantage:

“I was not the same person in Korea because, of course, I didn’t speak the language. I was made a baby by my ineptitude, or else, maybe I was simpler than I knew in the tricked-out language of my mind.”

The more people tell O’Neill about her mother, the less she knows. Stories crisscross, collide, and contradict. She’s also told her birth father is dead, alive, kicked her mother in the womb to cause an abortion, wanted to keep her, and wanted to give her up. She’s then informed that her birth mother swore she’d had a miscarriage and thought O’Neill had died.

Finally, the author meets her birth mother in person. Here, the prose is not kind as she compares the woman to a toy monkey, “hair more than a hint of mad cherry red, like a half-rinsed paintbrush above lit eyes: agrestal, possessed, and absent a few screws.” To O’Neill’s many questions, she claims to have no answers. She then immediately pressures O’Neill to get married, a common Korean fixation.

O’Neill flees, abandoning her birth mother the way she, too, was once abandoned. The final straw is the discovery that the woman has not told her favorite child, the youngest son, about O’Neill’s existence:

“I’d decided that I could abide my eomma’s dirty secrets when, as it happened, I was the dirty secret she could not abide.”

Grappling with the reunion, the author seeks to understand her experience by getting it down on the page, noting, “I write to demand for the encounter to have some meaning.” She realizes that her search for her mother was really “a search for home.” Crossing the precarious bridge to adoptee consciousness, O’Neill understands that family doesn’t have to be genetic or adoptive but can be chosen. That she doesn’t have to choose either/or, but can claim both/and. That not every journey is a straight line. That one’s story is never over but always evolving.

In the end, Woman of Interest is a shaggy-dog story. What starts as true crime devolves into an unknowable mystery. After the author finds the object of her search, the prose loses its cockiness, going from a spunky, nervy cheekiness to a vulnerable, philosophical meditation on family, storytelling, acceptance, and love. Her home is language; her destiny is to shape her own narrative.

Alice Stephens is the author of the novel Famous Adopted People. She is still searching for her Korean mother.

_1_80_120.png)