Can mainstream news outlets overcome their implicit bias?

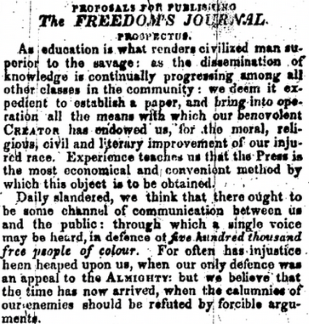

In the inaugural issue of John B. Russwurm and Samuel E. Cornish’s Freedom’s Journal, the newspaper editors made clear the purpose and perspective of the paper. On the very first page of the March 16, 1827, edition, they explained that they deemed it “expedient to establish a paper…for the moral, religious, civil and literary improvement of our injured race.”

It was for free Black people, like Russwurm and Cornish themselves. Its purpose was to bring enlightened education to the editors’ Black “brethren” and correct misinformation feeding the ignorance of Others outside the Black community. Freedom’s Journal would — and did — provide information on topics of importance to the free Black community. “Daily slandered,” the editors reflected, “we think there…ought to be some channel of communication between us and the public.” Experience had taught them that “the Press is the most economical and convenient method.”

Russwurm and Cornish’s concerns about the slander and injustices “heaped upon” Black Americans back then are all too familiar for today’s minoritized consumers of news. Many of us take mainstream news from even the most reputable and respected publications with a grain of salt. Misrepresentations of us are longstanding and as pernicious as Russwurm and Cornish’s 197-year-old mission statement suggests.

Minoritized Americans live in communities often painted by the mainstream media in one dimension. We participate in activities and attend events which are frequently distorted when put in print. The countries of our ancestral origin are all but ignored, as if those countries have no news at all. In fact, many of the things that matter to us — especially those things that counter preferred narratives — are given short shrift in the press. It’s painful.

There are few things more infuriating than experiencing the erasure of you and the mischaracterization of the people you know. There are few things more infuriating than needing to read culturally biased deficit narratives from otherwise reputable sources in order to stay conversant and informed on other current events.

For these reasons, I’ve been on a TV-news fast since 1992. That same year, I stopped reading the Washington Post, stopped looking for anything meaningful about my community there, started reading the Black-owned and operated Washington Informer instead, and began my lifelong practice of mitigating racial/cultural bias by reading several sources on the same topic. Back then — new to Washington and active around Shaw and on Howard’s campus — I could not trust the Post like I wanted to. Amid its otherwise excellent reporting, there were too many discrepancies between what I experienced firsthand and what I read about it later. There was too much negativity in the “prestige press” about every place that I saw in its rich complexity.

Fortunately, there are many more options for minoritized readers to balance our news intake than there were in ‘92, and the news giants have improved. Notably, they have also begun to talk about their problem. In 2021, the New York Times published “How the White Press Wrote Off Black America,” which surveyed the history of anti-Black racism in newspapers and chronicled recent apologies. And the Post published the insightful reflection “The Black Press Provides a Model for How Mainstream News Can Better Cover Racism” in 2020. It notes:

“The work of Black journalists is a model for how newspapers today can better cover sensational, headline-grabbing incidents of racist violence and racial injustice: putting them in social, political and historical context, giving them sustained attention and questioning the official narrative of events. Mainstream newspapers today might also glean something from the contemporary Black press, which has always taken Black audiences and Black experiences seriously. No racial reckoning in mainstream news organizations can be undertaken without doing the same.” (Emphasis mine.)

Despite improvements among all major newspapers, they are still culturally biased in many ways. Members of the National Association of Black Journalists are still “striving for credible journalism that comprehensively portrays the voices and experiences of African Americans and people from the black diaspora for a society and world that values them,” according to the organization’s 2023 Constitution. The National Association of Hispanic Journalists exists today, in part, to “foster and promote the fair treatment of Hispanics in the media.” They have even written a Cultural Competence Handbook (2020) in support of news journalists willing to reflect on their practice and grow in their “ability to understand, appreciate and interact with people from a broad range of backgrounds, experiences and viewpoints with respect.”

As far as inclusivity and representation go, the mainstream press is still very much a work in progress. But its calls for racial reckoning seem a little quieter these days, especially when compared to the alarms it is sounding about fake news and truth in reporting. Today, the press finds itself in the position of defending truth itself, as it is now sharing readership with websites propagating fake news and misinformation.

It is also concerned about keeping the rigorous field of journalism alive. According to Forbes, nearly 3,000 local newspapers have closed in the last 20 years. Understandably, worries about staying afloat and the clamor over the “post-truth era” problem of propaganda may drown out appeals to resolve old concerns. However, I’d like to see a convergence of reform efforts — the re-entrenchment of journalistic ethics alongside a renewed commitment to inclusivity and diversity of representation.

Since racial/cultural bias in the media is a form of misinformation, today’s discussion of post-truth misinformation must itself be critically analyzed. For example, the term “post-truth” — used by people in journalism, education, and library studies to bring the problems of misinformation to light — may itself be a bit of a misnomer. To me, it suggests that reporting used to be truer than it was. Most professionals who use the term mean it to refer to the current milieu, which exists after the one in which truth mattered. The term invokes a time in media and education when truth — as opposed to group identity, political affiliation, and readers’ feelings — was supposedly the central reason for writing and reading.

But again, that era was also a time of overwhelming Eurocentric, patriarchal, hetero-centric, and classist mono-perspectives. Thus, when I teach and write on the phenomenon, I name our current era as both epicolonial and post-truth. But that’s clunky, and I’m open to suggestions on how better to describe the problem. So far, Stephen Colbert’s “truthiness” seems best suited to cover both aspects of the problem, and the phrase “true and inclusive” works alright for envisioning something better than what we had before.

The warriors of journalism who have trained their sights on internet propaganda are doing nothing less than seeking to save their profession and democracy itself, which indeed “dies in darkness,” as the Washington Post reminds us daily. As Russwurm and Cornish knew then, and the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) reminds us now, “public enlightenment is the forerunner of justice and the foundation of democracy.” As the SPJ also says, “Ethical journalism strives to ensure the free exchange of information that is accurate, fair and thorough. An ethical journalist acts with integrity.” Thorough includes diverse perspectives, and integrity requires self-examination for cultural and racial bias.

The “good old days,” before criticality and inclusivity, weren’t good enough, as a quick re-skim of Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky’s classic Manufacturing Consent (reissued in 2017) makes plain. Their simple framework for analyzing media bias — including racial/cultural bias, as many post-truth critics don’t — is just as relevant now as it was in 1988, when the book was published.

As the authors said back then, the ownership of news outlets, the interests of the advertisers in them, the sources their journalists access, the degree to which an outlet gives “flak” to divergent viewpoints, and the degree to which they marginalize dissent still matter. Anyone echoing the romanticized, nostalgic tropes about the golden era of the press should self-examine and seek higher standards — even, or especially, as they seek to bring sanity back to news reporting.

Sarah Trembath is an Eagles fan from the suburbs of Philadelphia who currently lives in Baltimore with her family. She holds a master’s degree in African American literature and a doctorate in Education Policy and Leadership. She is also a writer on faculty at American University. She reviews books for the Independent, has written extensively for other publications, and, in 2019, was the recipient of the American Studies Association’s Gloria Anzaldúa Award for independent scholars for her social-justice writing and teaching. Her collection of essays is currently in press at Lazuli Literary Group.