Can the second half of a woman’s life actually be kind of great?

The prime years of a woman’s life are bookended by two predicaments: entry into the fertile era (replete with pads and tampons, irritability, and cramping) and exit from the fertile era (teeming with hot flashes, sleep problems, and bone fragility). For men, things are less exciting.

In the recent past, I began wandering the halls of perimenopause with less information at hand than ideal — which is to say, no information at all. This is not surprising since I’ve been in the camp of those who’re in denial of the natural process of aging. The few people I’d accidentally spoken to about this stage explained to me that menopause descended on them gently and swiftly. So, I was shocked by the headaches, mental fog, disrupted sleep, and other problems I encountered.

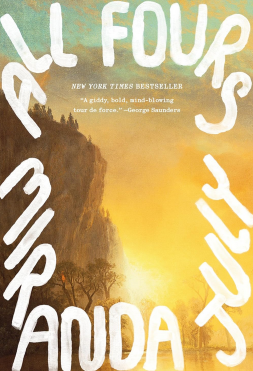

Just at this unexpected juncture of my life, I heard about a new book getting rave reviews and being touted as “the first great perimenopause novel.” The coincidence was almost too much: I was in perimenopause just as Miranda July’s All Fours was published. I immediately downloaded it on Audible and waded in.

(The next section has spoilers, so please proceed with caution.)

I swallowed the book in one quick gulp, propelled by the main character’s boldness (or recklessness), passion, and vulnerability. The unnamed protagonist and a younger man she has little in common with have an intense emotional affair, which opens the door for her to leave her marriage and redefine her future on her own terms, even if it’s uncertain and not particularly delightful.

What was most impressive about the book was how July created a middle-aged protagonist as intriguing as any literary character I’ve encountered. It made me realize how few such figures there are in fiction. But is it really a surprise that female characters who are “in the middle of their life,” as July puts it, have had very limited space in the canon?

Art imitates life, after all. And so July, in clear rebellion, set herself the task of creating a protagonist who will leave an indelible mark on readers’ minds. Of course, the character looks younger than her age, is famous, and has an obsessive streak. In other words, she’s not exactly the woman next door.

While fascinating, the book isn’t a perimenopause novel so much as a novel about a character who happens to be going through perimenopause. If I’d hoped to glean from it any insights into my own state, I wasn’t especially enlightened. But that’s not to say there weren’t some important takeaways. For instance, some of the protagonist’s older friends tell her that they’re better off after menopause. (A woman’s life must truly suck if the time when people stop noticing she exists is the best time in her life.) In a similar vein, a doctor friend tells her that a woman’s mental health improves in menopause.

Ultimately, the book is inspiring. The protagonist doesn’t sit on the sidelines but decides to take control of her life, even if it means blowing up several seemingly good things. She doesn’t quietly shrink and fade into oblivion. She takes up space. And she’s able to do all this because she finds herself interesting.

She matters. And that matters.

Ananya Bhattacharyya is a Washington-based editor and writer. Her work has been published in the New York Times, Guardian, Lit Hub, Baltimore Sun, Al Jazeera America, Reuters, Vice, Washingtonian, and other publications.